Nostalgia is a powerful drug, and I might just be high off a memory, but in my educated, debatable opinion, Henry “Gizmo” Williams gave us the greatest individual play in a championship football game, ever, in the 1987 Grey Cup.

Better than the Philly Special in Super Bowl LII; better than Rocket Ismail leaving the Calgary Stampeders in his vapour trail in 1991; better than Ronnie Lott knocking Ickey Woods senseless to turn the tide in Super Bowl XXIII.

A 46-yard field goal attempt by Toronto’s Lance Chomyk drifted wide right, and into the hands of Williams, whose 5-foot-6 frame rippled with 185 pounds of fast-twitch muscle, and who still might be the greatest return man any form of this sport has ever seen. The record book says the subsequent missed field goal runback was 112 yards long, but video hints that Gizmo covered at least 150.

First score in a title game that Edmonton would win 38-36, and a feat I point to as proof that skill position players need speed beyond the 40-yard dash. Williams ran 10.2 and 20.8 in college, if you’re wondering.

More importantly it’s the kind of play that can only unfold north of the border.

Williams could have taken a knee so his team could start its next possession at the 35-yard line. All it would cost him was a single point, the current cost of a touchback under Canadian rules. When you’re playing for field position, you make that tradeoff.

But if you saw Williams play, you know he was better than instant field position. He had the speed to warp outcomes.

Williams hit the nitrous, and we all saw the result. Six points the other way. An eight-point swing in a razor-thin game. A sequence as Canadian as Joey Jeremiah’s jean jacket.

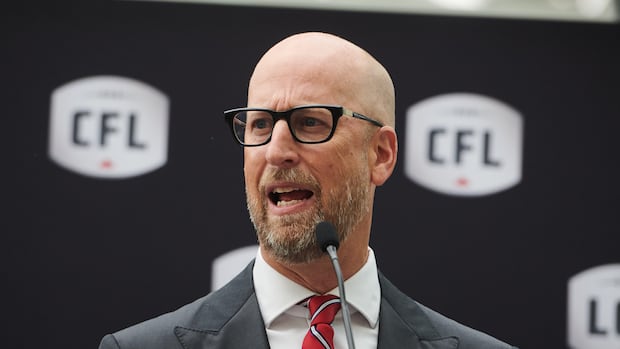

WATCH | CFL attempts to boost popularity:

‘It’s time for some change,’ former CFL star Bryan Chiu says after the Canadian league announced rule changes to improve its game and make it more entertaining for fans. Among those changes includes a shortened field and restricting how single points are awarded.

Fundamentally Canadian quirks

In 2027, the rule that facilitated Williams’ breathtaking run will disappear, as the CFL introduces changes to some of the three-down game’s fundamentally Canadian quirks. The distance between goal lines will shrink to 100 yards from the current 110, while endzones, which are 20 yards deep right now, will downsize to 15. Goalposts will move from the goal line to the back of the end zone, and the single point awarded for a missed field goal not returned will vanish.

It’s a bold series of moves, aimed at juicing the action and attracting new fans to a league in which only two of nine teams – Winnipeg and Saskatchewan – turned a profit last season.

I’m not married to the rouge, but I love the possibility of a coast-to-coast missed field goal return, and any other quirk that marks three-down, big-field, Canadian-style football as distinct. Any move that nudges the CFL closer to the NFL’s rule set risks alienating people who already love Canadian football, with no guarantees that new fans will replace them. In the age of rampant sports gambling, it looks like a big bet with no clear payoff.

I recognize there’s no sense in comparing the CFL with the NFL. Different leagues, different countries, vastly different marketing puzzles to solve.

The NFL’s dilemmas tend to be good problems. They have aggressive revenue growth goals and a saturated domestic market, and a couple of ways to expand their massive fan base.

One involves luck – a star player strikes up a relationship with a pop music icon, and suddenly the league inherits millions of followers. That’s a long shot for the CFL, unless you find a football player and a multi-platinum singer each comfortable dating way outside their tax bracket.

And the other involves exporting the product – to Brazil, Germany, England and Ireland. A non-starter if you can’t even get a critical mass of domestic fans hooked on your game.

But before we contrast the leagues, a reminder:

Football is mostly people standing around. The action happens in seven-second bursts, and the rest is what famed high school track coach Tony Holler calls “televised loitering.”

That setup makes football an ideal broadcast vehicle – all those stoppages in play make room for advertising – and a dreadful broadcast product. The average U.S. college game now consumes nearly three-and-a-half hours of airtime, while a typical NFL broadcast includes 100 ads and 11 minutes of game action.

It’s bad TV that happens to do big ratings.

In both those forms of football, rules are a variable. The NFL has tinkered with its kickoff alignment and changed its overtime format. College ball now features automatic touchbacks, teams with pro-style payrolls, and conferences that change members almost annually.

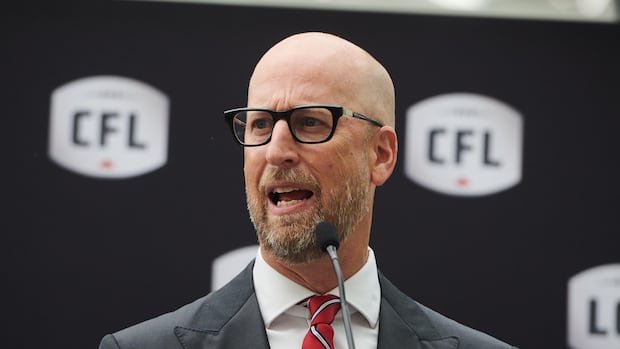

WATCH | CFL changes bring an NFL look to the field:

The Canadian Football League has announced several changes, including a modified field size and relocated goal posts that many say create similarities to the NFL, something the CFL commissioner says wasn’t the intention.

No magic rule tweak

But you know what’s constant in that equation?

Popularity.

Front Office Sports reports a surge in early season college football viewership, while nearly 34 million people tuned in to a recent Eagles-Chiefs matchup.

Those details tell you that there’s no magic rule tweak that can vault your league from afterthought to appointment viewing, or cause die-hards to abandon you. As much as those numbers reflect the entertainment value of the on-field product, they’re also a function of habit, tradition and perception. New rules probably don’t solve that problem. Marketing might.

That’s another uphill struggle for the CFL, which can’t outbid the NFL for elite talent, or turn its draft into a weekend-long street party. But the beauty of the CFL, traditionally, is that it provides a platform for outstanding football players who happen not to fit an NFL template.

Sometimes it’s a function of hiring habits. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when NFL teams hewed to unwritten rules against drafting and playing Black quarterbacks, CFL teams put those standouts to work under centre. The first Super Bowl to feature two Black QBs happened in 2023; the Grey Cup did it in 1983.

And sometimes it’s a function of the rules and plus-sized playing surface. When the NFL ignored smallish, quick-thinking pivots who could throw on the move, players like Doug Flutie and Jeff Garcia put up huge numbers in Canada.

Then there’s Williams, a serviceable return man in his lone NFL season, but dynamo in the CFL, where a five-yard halo protects punt returners, and where missed field goals provide another chance to electrify audiences.

Yes, all those players are long retired, and, no, the CFL can’t return to its melon-blazer glory days. But the league can continue leaning into the uniqueness of the Canadian game.

Source link